I’ve lived in Boston since 1986, but have never made it into the great Boston Public Library. Until today. My streak was totally broken because the little group digitizing the BPL’s holdings invited me in to see what they’re doing. And, oy, the work they have cut out for them!

But they’re an intrepid band. And they recognize that they’re up to something important. Although some in the BPL may have thought that digitized prints and photos are just lesser-qualities backups, the group knows that they’re not only bringing hidden images into the public sun, they are engaged in a social project that changes how and what we know. (What’s not to love about librarians?)

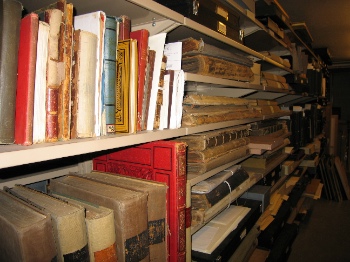

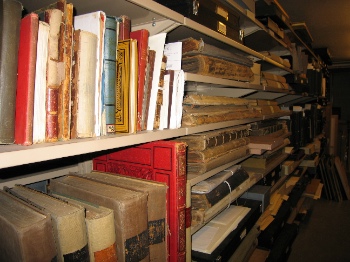

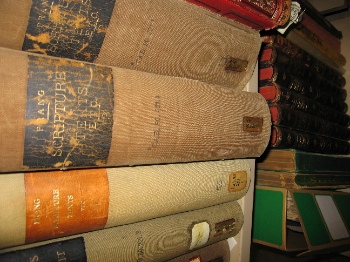

The Print Stack, where photos, prints and miscellaneous other objects are stored, only seems to be in the basement. The ceiling is low, there are now windows, and the lighting leaches vitamin D out of your body. It’s long and overflowing, reminiscent of the warehouse that ends Citizen Kane, and that is echoed in two Indiana Jones movies.

If you want to find a particular image in the roughly two million prints and images (no one knows for sure), you ask Aaron. Some bits and portions have catalogs of various sorts, but overall, it’s a disarray of metadata. For example, the Herald Traveler collection of photos has about 1.2 million pieces, arranged in 104 cabinets, each with four drawers. The folders and drawers are labeled, which helps a lot, but they’re not indexed, much less cross-indexed.

Herald Traveler collection

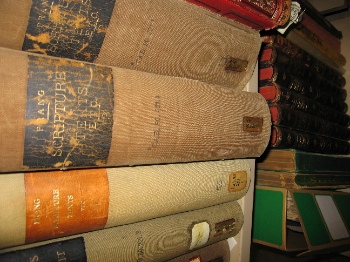

At least those photos have captions. Aaron shows me some beautiful 19th century photographs of Indian architecture. Many years ago, the BPL went to enormous trouble to paste the photos into multiple volumes — turning the photos into a book, as Aaron points out — but didn’t bother to record the notes on the back of the photos. Aaron is now going to have to dissolve the pages to expose the notes.

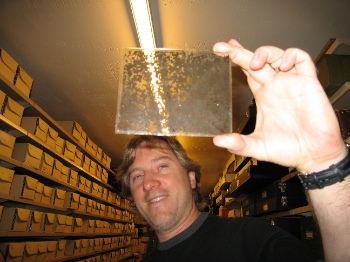

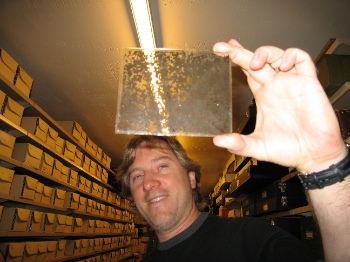

Aaron holds up a degraded negative.

A dirigible is barely visible on it.

Tough reclamation project.

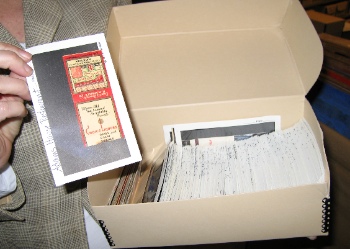

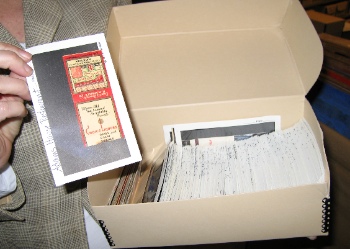

The archive doesn’t just have pictures and prints. It’s got, well, everything, including a couple of old typewriters and a collection of matchbook covers from Boston restaurants.

Boston matchbook cover collection

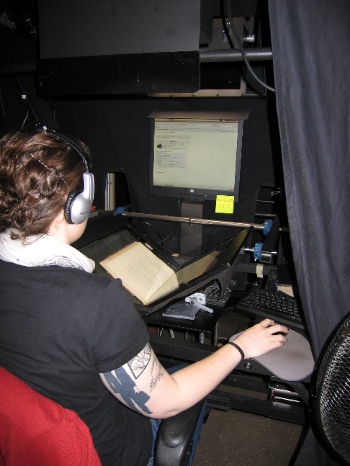

Of this abundance, the digital group has so far scanned about 24,000 objects. When I point out to Maura Marx, the group’s head, that, given the library’s estimate that it has maybe 23 million objects, she’s looking at a 2,000 year project, she tells me that they’re just getting started. They’re going to bulk up, maybe do some offsite digitizing, and begin to make some serious progress. When I ask Thomas Blake, who does the actual digitizing, how he decides which stuff to do, he laughs a little and says, “What I think is cool.” And, since the public has an appetite for “choochoo trains, maps and postcards,” he’s done a bunch of them. The BPL is, after all, a public institution that both serves the public and relies upon the public’s support.

The Library has been posting digitized works at Flickr. Take a look at the 19th century photos of Egypt, or, yes, the postcards And the book fetishists among you should definitely check out the “Art of the Book” collection. Predictably and hearteningly, the public — you and me, sister — have been commenting and adding to what’s known. Maura hopes to get permission to put the images into the Commons. Digitizing and posting — “scan and release,” in the group’s memorable way of putting its mission — turns patrons into historians.

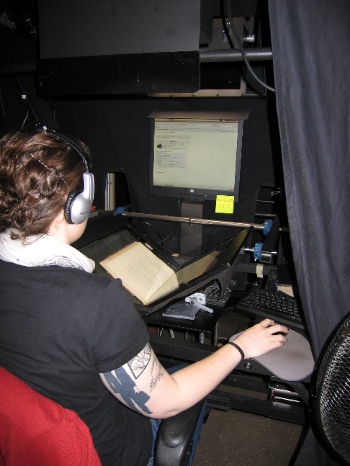

The scanning is slow because it’s one guy who’s doing a careful job. The camera has a 22 megapixel chip, but they’ve been known to digitize at 88mps, creating files that are half a gig in size. Tom likes saving the RAW files to avoid unnecessary data loss. You never know what’s going to be useful. For example, he had been scanning postcards at 300 dpi, but a curator pointed out that then you couldn’t see the dotscreen pattern, which might be of interest to someone. So now Tom scans them at 600dpi. Overall, they have about 1.5 terabytes of stored images.

The metadata is a whole ‘nother issue. Chrissy Watkins, who has been there for four days — she had been at the JFK Presidential Library — is working on it. For now, Tom gives every item an arbitrary and unique ID number, the key piece of any metadata scheme. But the BPL is facing the inevitable conundrum: Maximize the metadata but slow the process, or do grave less metadata but go at a far faster clip. The group seems to be leaning toward the latter, which makes sense to me. They’ve been using what Tom calls the “Curator Core,” a reference to the Dublin Core metadata standard for books. Trying to capture everything that might be useful is a task beyond daunting. For example, Michael Klein points to “fore-edge paintings,” paintings done on the edges of a book that are revealed when you fan the book slightly. Does the BPL have to come up with a standard that includes whether you fan the book to the left or right? There are so many different types of objects that building a standard or an ontology that captures them all would absorb all of the team’s time. (”The special case is not as special as you’d think,” says Michael.) Instead, they need to scan scan scan, and capture some reasonable set of metadata, to which more metadata can accrete.

One of the ten Open Content Alliance book scanners.

“We’re going from collect and hide to scan and release,” says Tom. And in so doing, they’re going not just from no value to some value. They are in fact radically multiplying the value of the Boston Public Library’s holdings. And as we the recipients of this gift incorporate the images, adding information to them, and contextualizing them, we are further enriching the holdings, far beyond what any small group, no matter how intrepid, could manage.

[Tags: libraries bpl metadata oca archives everything_is_miscellaneous ]